[…] When she lived in Iran, Valian was a celebrated mountain climber and member of the women's national climbing team: "A Woman as Steadfast as the Damavand Peak," is how she was presented in a state-run women's magazine in 2009. However, she was keenly aware that such praise was intended only for public show: in real life, no matter how celebrated, female athletes are still treated unequally, like all women in Iran. While Valin's experience of discrimination is one that is shared by millions, her narrative gains additional resonance due to her dual role as an athlete and artist.

Born in 1977 in Shahroud, Semnan province, Valian comes from a modest family. As the second daughter in a family of six, she soon became conscious of the vulnerability of women in society. She describes growing up in the conservative city, with the ever-present morality police and the regime's propaganda blaring from loudspeakers and plastered across the walls of buildings. As a child, she witnessed brutal public punishments. She knew, too, that early morning calls to prayer, the adhan, sometimes signaled impending public hangings. Later, on her way to school, she would see authorities dismantling the gruesome instruments of execution while passersby looked on, some in shock and others in approval.

These unsettling realities popelled valian toward sports, to fortify her body also, she hoped, to find a brighter future. She initially joined her school’s vollyball team, but took up mountain climbing after enrolling at Mashhad’s university’s School of Art, one of Iran’s premier institutions. While volleyball had submereged her in teamwork, mountain climbing provided solitude, forcing her to confront her reality both as a woman and a human. The challenges of scaling mountains like Alborz, which she conquered in record time, hond her resilience.

While Valian's athletic achievements soared as part of trans national climbing team, her personal life was tumultuous. After a short-lived relationship and marriage in Tehran, she focused on her dual passions: sports and art, the latter manifesting in her work as a high school teacher and private tutor. Her rigorous training and adventures transformed her physique, sculpting her into a beacon of strength and beauty. She learned survival skills on climbing expeditions in the Himalayas, using the warmth of her body to combat the bone-chilling temperatures at high altitudes. Yet, even under the extreme conditions, Valian confronted vulnerabilities: not only did she have to negotiate the dynamics of being in close quarters with male climbers, she also had to grapple with societal perceptions of women's roles and desires.

At the height of her athletic success, Valian was sexually assaulted in Tehran. The experience left deep scars. Though immensely strong, she chose not to fight back, fearing that if she injured her assailant she would face the same kind of fate as Reyhaneh Jabbari, an interior design student whohad defended herself — with fatal consequences - when she was sexually assaulted by a potential client who took her to an empty apartment for a work-related matter. Jabbari was imprisoned for seven years and then executed, despite international appeals for clemency. The chilling tale, later the subject of the film Seven Winters in Tehran (2023), resonated with Valian back in 2007, long before it made global headlines. For Valian, Jabbari's ordeal is not an isolated occurrence, but representative of the many hidden stories of women's plight in Iran. She believes the regime used Jabbari's prolonged incarceration and eventual execution to convey a chilling message: that women, irrespective of the circumstances, remain perpetually vulnerable, and should always submit rather than defend themselves against male aggressors. As she puts it: "This is a calculated subjugation of women and a tacit endorsement of all men, whether virtuous or vile."

These traumas permeate Valian's art, which address themes of sexual harassment. Her work is further influenced by particularly disturbing encounter with the morality police during a public religious procession on the Day of Ashura in 2006. After an exhausting practice, Valian was returning to her apartment without her required trench coat when she unintentionally neared the procession. There, she was confronted by an agent who spewed threats of violence— he thought she should be put in a sack and abandoned in the desert outside Tehran-because of her attire. Haunted by the experience, Valian collaborated with California-based artist Sarah McCarthy Grimm on a lengthy poem, which they performed at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco while wrapped inside rice sacks. Valian's portion of the poem, set in italics, tells the story of a young girl, her secret mirror, the objects in her room, and her struggles with the brutality of the men in her life. The poem appreciates the objects in her room in these words: "Thanks objects; thanks objects for not being human; thanks objects for treating her humanely." McCarthy Grimm's part, in roman type, describes her experiences assisting victims of sexual violence in Argentina, Uganda, and Guatemala. Titled Detained Imprints, the performance reenacted women's experiences, reminding us that the life of a celebrated athlete can resonate with the struggles of everyday people.

If reenactment is essentially a performative replication of life's struggles and conflicts, then documenting these realities, especially during the height of the uprising, is a significant contribution that deserves recognition. While the documentation undertaken by Iranians in the diaspora is often rooted in academic, archival, or publishing backgrounds, and compiled retrospectively, the documentation by artists in Iran tends to be more immediate and spontaneous.

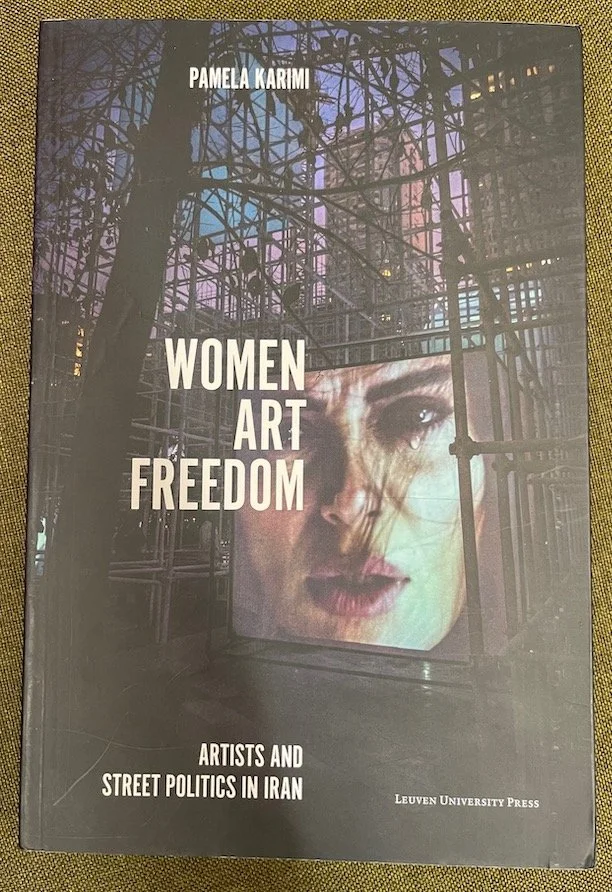

Badri Valian during the peak of her career as a member of Iran's Women's National Mountain Climbing Team, October 2008

Badri Valian and Sarah McCarthy Grimm, Detained Imprints, performance at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California, 2023